by Earl Guen Quiñones Padayao | March 11, 2023

There were multiple attempts in history to write a charter for students’ rights in the Philippines. A deeper look into this history will show that some members of our national legislature took notice of students’ rights – yet for one reason or another – political or otherwise – these bills find it hard to get through the legislative mill.

In this column, I will introduce a review of legislative history that would reveal that the idea of a student’s rights Magna Carta already piqued the interest of multiple generations of legislators. However, as evidenced by the apparent absence of such a charter to date – mere interest failed to deliver.

Students’ Rights and the Senate

In the Senate, multiple bills were filed to codify students’ rights. According to Former Senator Francis Escudero, the history of the Bill dates back to the 8th Congress. However, a more careful review of records would reveal that it traces back to the 6th Congress as early as 1969.

It was registered as Senate Bill 772, otherwise known as ‘Magna Carta for Students,’ introduced by the late Senators Eva Estrada Kalaw and Benigno Aquino Jr. This is the oldest students’ right Magna Carta bill. Professor Joseph Scalice described it as an attempt by Aquino to channel and win the support of the emerging student unrest.

However, the Bill failed to “address the skyrocketing tuition rates and crumbling infrastructure that set off the 1969 explosion.”

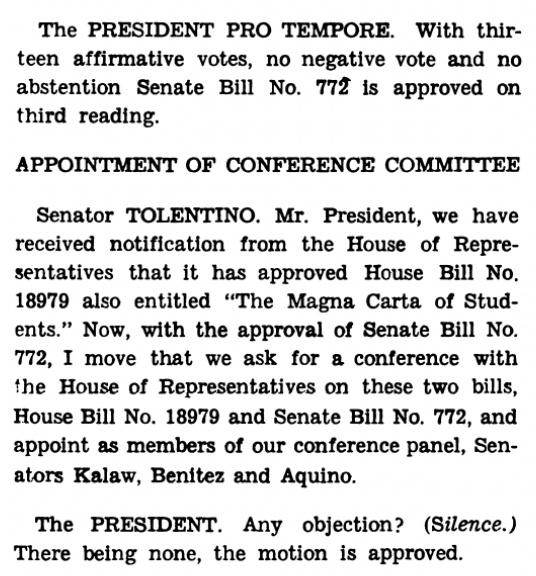

On June 2, 1969, the first Magna Carta for students bill was approved on the third reading with thirteen affirmative votes, no negative votes, and no abstention.

It could be observed from the chamber composition that notable legal luminaries were part of this senate generation. The likes of Jose W. Diokno, Jovito R. Salonga, and Arturo M. Tolentino. It also appears that the lower house approved a bill of the same title. Hence, the versions of both the upper and lower houses were referred to the bicameral conference committee. The following scanned portion from the archive shows this observation:

Republic of the Philippines, June 2, 1969

The Enrolled Bill was later vetoed by the Late President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. on Aug. 4, 1969. The veto was inspired by strong opposition to the Bill as students denounced and labeled it as a “Magna Carta for School Administrators.” Students reportedly staged protests against the Bill. Dr. Nemesio E. Prudente, President of the Philippine Association of State Universities and Colleges (PASUC) interposed one key opposition to this bill.

In recent history, another Estrada filed a bill of similar breath. Senator Jinggoy P. Ejercito-Estrada filed a Magna Carta for students in 2010, but it never left the committee. In 2013, Senator Loren Legarda filed a bill that seeks to create a national policy to promote and guarantee students’ rights and welfare. In the same year, Sen. Cynthia Villar also filed a bill providing for a Magna Carta for students. Senator Francis “Chiz” Escudero co-authors the Bill. A year later, Senator Paolo Benigno Aquino filed Senate Bill 2369, which also seeks to codify students’ rights and welfare. All of which never passed into law.

In 2019, Senator Risa Hontiveros filed Senate Bill 361, which again seeks to establish a national framework for students’ rights and welfare. Two years had passed, and with her term ending, the Bill had not left the committee.

Clearly, the Senate has realized the void left by the absence of this Magna Carta. The relevant portion of the explanatory note of the Senate Bill 361 is apropos:

“With the lack of a national policy to uphold and defend the rights and interests of students, campuses may cease to be a space for genuine education. Students are in danger of being alienated from democratic processes, and their role in nation-building may be compromised. Schools should provide a climate conducive to both learning and empowerment. Thus, there is a need to protect students from an educational system that violates their rights and neglects their welfare.”

Students’ Rights and the House of Representatives

The lack of legislative success in codifying students’ rights is not exclusive to the Senate. The House of Representatives shares the same.

After the vetoed Bill of 1969, the next notable attempt in the lower house was in 1997. Rep. Edcel Lagman, et.al. filed House Bill No. 9935. Yet, the Bill was faced with major opposition. The Manila Times even labeled the Bill as the ‘Magna Carta of discord.’

House Bill No. 9935 was heavily criticized by the private education sector. Bro. Andrew Gonzales, then president of De La Salle University, wrote:

“Private colleges and universities in the Philippines were closed late last year for a day of silent protest. Following the Oct. 12, 1997, congressional ratification of a "Magna Carta" for students (House Bill Number 9935), the country's Coordinating Council of Private Educational Associations (CCPEA)—a national federation of sectarian and proprietary colleges and universities—called for the action to make public their concerns about several provisions in the new Bill. Administrators of the country's almost 1,000 private colleges and universities fear that the student Magna Carta could jeopardize their ability to manage and to keep schools viable.”

The Bill’s controversial status even pushed then-President Fidel V. Ramos to step into the negotiation table. He “called for a series of meetings with legislators, students, and college administrators in an effort to iron out differences and reach a compromise on the more objectionable features of the Magna Carta.” The Bill never became law.

The next attempt was in the year 2000, House Bills Nos. 180, 4003, and 6174 were filed by Representatives Ranjit Ramos Shahani, Krisel Lagman-Luistro, and Imee R. Marcos, respectively. The Commission on Human Rights (CHR) commented on its opposition to some provisions of these bills on a position paper, expressing concern over some provisions which go against settled principles and standards set by jurisprudence.

From 2013 to 2014, House Bill No. 2870, another Magna Carta for students bill, was filed and lobbied by Rep. Diosdado Macapagal Arroyo and Rep. Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. Diosdado stressed that the proposed law will “set forth in unequivocal terms, the rights and responsibilities of the student-youth from the secondary level to the post-secondary and tertiary levels of education, including vocational and technical education.’ In 2016, Rep. Alfred Vargas filed House Bill No. 4509, which seeks to provide a national framework for students’ rights and welfare. None of these bills became law. In 2019, Rep. Sarah Elago filed at the House of Representatives a resolution that urged the members of the chamber to uphold a ‘Philippine Declaration of Students’ Rights.’

The most recent development happened on March 18, 2021, when Rep. Manuel Antonio Zubiri filed House Bill 9359, titled ‘Magna Carta of Students Rights and Welfare Act of 2021.’ The Bill is currently pending at the House Committee on Basic Education and Culture. The explanatory note of House Bill 9359 is apropos: “Currently, there is no standard or law that upholds student rights throughout the country. As such, school administrations have powerful authority with regard to disallowing students from exercising their right to organize, and enforcing harsh disciplinary action against students who dare speak their minds. It has become the prerogative of schools to enact their own rules and regulations, at times without fully considering the basic rights of their students. The need for a Magna Carta for Students is evident. Students who want to involve themselves in demonstrations or organized protests should be given the freedom to do so and not be subjugated by administration policies and regulations. A Magna Carta for Students will protect the Filipino youth, and empower them to become outspoken, socially involved individuals who are attuned to the problems of the nation and devoted to finding solutions for them.”

As it stands, we do not have a national legislative framework for students’ rights without our own special Magna Carta.

What does the future hold for students sans adequate legal protection? Alas – a question for the philosophers.