By Issachar Bacang

Saying “this is my authentic self” online is a big oxymoron.

Authenticity is a necessary lamb to sacrifice for the privilege of being online in any acceptable manner. We are in an age wherein we as people live simultaneously in two realms: one real and one digital.

At the entry point of the digital realm, we are greeted by an altar that promises things we can do with our image that we wish we could do in real life. In real life we are condemned to be ourselves, to be actually ‘authentic.’ People can see us—all our imperfect, unsavory, unlikeable angels, facets, and moments. In real life, people can hear you talk, can see the way you treat others, know what you really look like, they can smell you, sense you. All this, save for an impossibly perfect person, we wish we could change or at least alter in some small way.

Online, however, the pagan god of virtuality offers you the chance to reinvent yourself in a way you find most ideal. You are the little mermaid, and Ursula offers your poor, unfortunate soul legs and a life on land—to be perfect for your prince—in exchange for what makes you real, what makes you ‘you:’ your voice.

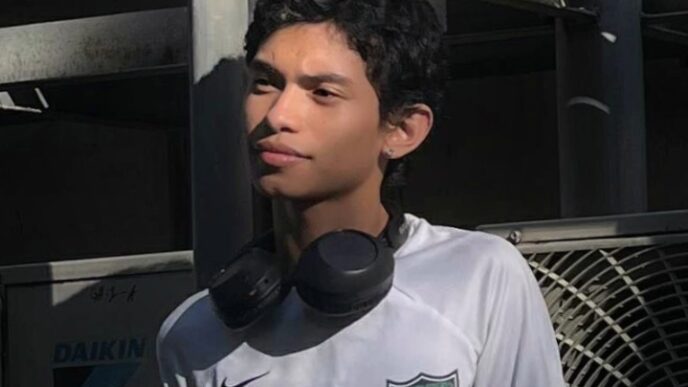

I’ve seen far too many of these tales floating around. I’ve known them both before and after they blew up on Instagram—men and women alike. Polished, perfect, unbotherable monsters. All of them once mild mannered and insecure, but undeniably real: teenagers. This is not to suggest that everyone online is actually a monster, or is currently embroiled in a scandal. The offer of changing destiny, or at least how the majority perceive you to be, is an offer every young teenager was given when they made their first Facebook account. And it’s an offer all of them took.

Those who are able to balance their real and online lives, and are able to anchor their identities to who they really are leave unscathed. They’ve cheated Ursula out of her deal. But I wouldn’t be writing this if the opposite were untrue. We don’t mean for it to happen. But suddenly we’re called out for something that happened in real life or for a secret said in confidence. We respond, of course, to defend our honor. Then we find that more people know us online than they do in real life. But because we’ve involved ourselves in a situation where we were called out, we respond online.

It’s here we find that there are very few in real life who would bother to know us there, much more defend us—where it actually matters. What’s worse is we find ourselves fighting for our lives, our good name—online—where we were never really who we were in the first place.

My message is of caution. My message is an invitation- to emerge from Plato’s cave and suffer the light of real life once again. If you refuse, I cannot stop you. But please rethink that pose. Tell yourself, overtly: “you probably shouldn’t post that…”