By Cynthia Shank

We all have our first picture somewhere in our phone’s gallery.

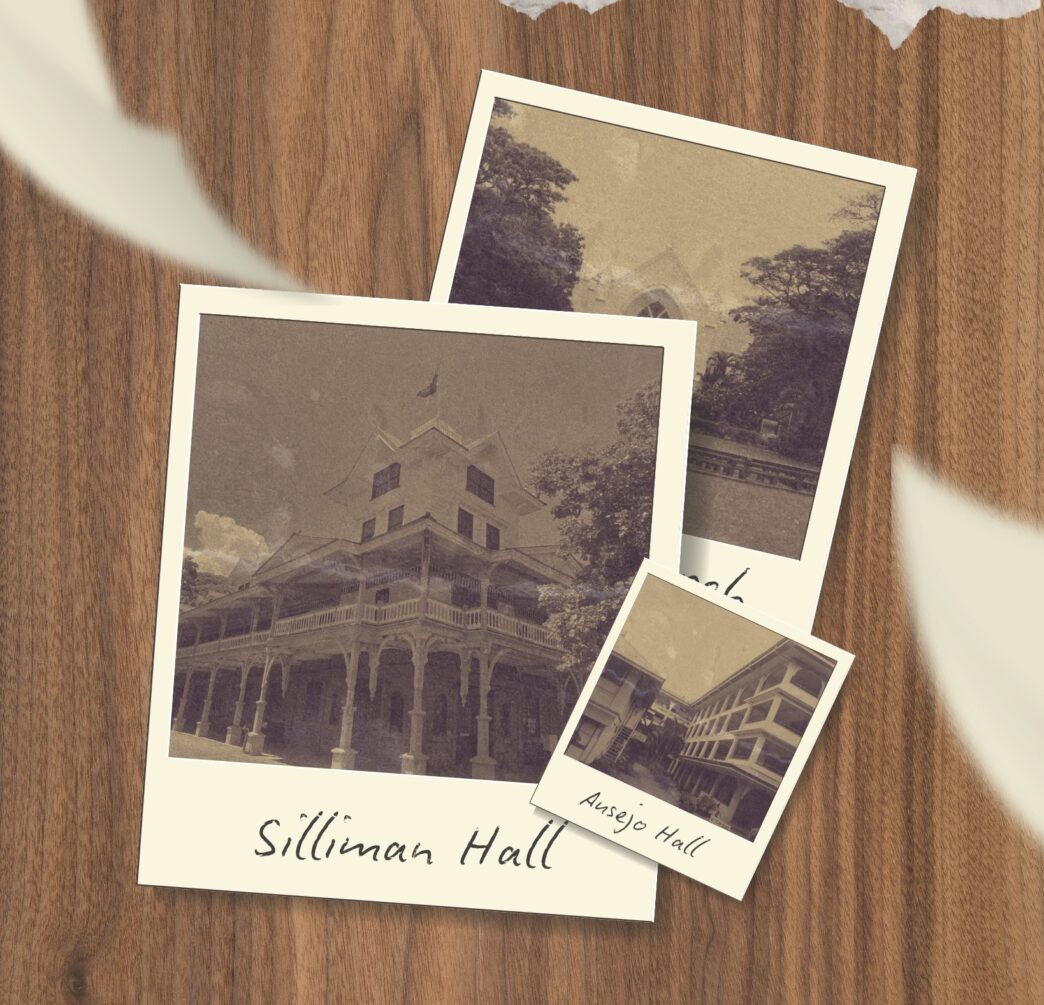

Maybe it’s a blurry shot taken by a nervous freshman on their first day in Silliman, the sea breeze catching the tree branches swaying away in the background, or it’s a hurried selfie outside the gates, the kind with the bronze Silliman University letters in the background and a caption like “Hello, college life!”

And somewhere down the line, we all take one last picture, though we rarely know it’s the last until long after it’s saved to a folder we barely open.

When I pitched this feature—“First and Last Photo Taken”—I imagined an album of beginnings and endings. I pictured my fellow Sillimanians sending me snapshots of their first wide-eyed days and their final bittersweet ones or current ones.

But the replies never came. My inbox stayed quiet, the deadline looming.

At first, I panicked. How do you write about other people’s photos when no one sends you any? But the silence started to feel like part of the story. Maybe those pictures aren’t meant to be published. Maybe the real point is that every Sillimanian already carries these first and last moments, even if they’re never shared.

The first photo might not be the one you posted. It could be the test shot your roommate took while checking the light in your dorm room. It could be the ID photo you hated. It could be a sunset over the boulevard you snapped to calm your nerves before orientation. That image, whether printed or pixelated, marks the exact second you began a chapter you couldn’t yet read.

The last photo is trickier. It might be a group shot after a thesis defense, or a candid from a farewell dinner you thought was just another Tuesday. Maybe it’s an empty classroom, desks gleaming after the janitor’s final sweep. Or maybe it hasn’t happened yet—you’re still here, still collecting light.

That’s the quiet lesson of first and last photos: we rarely recognize the endings as they happen. Life doesn’t shout “final frame.” It just keeps moving until one ordinary snapshot becomes the period at the end of a sentence.

Silliman itself teaches us this. Every acacia leaf that drifts to the ground is both an ending and a beginning. The sea along the boulevard never holds the same shade twice, and even the Luce Auditorium lights that feel eternal eventually dim after every end of the performance.

We dwell on two random pictures because those invisible bookends tell us something about who we are becoming and who we once were.

The first photo is proof of courage—it’s the moment we arrived, uncertain but willing. And the last photo is proof of change. The quiet evidence that we are leaving with more than we came with: friends, bruises, stories, and maybe a deeper version of ourselves.

Who cares if we never got the gallery we wanted?t Maybe that’s better.

Instead of scrolling through other people’s milestones, I hope you pause and scroll through your own camera roll. Notice how the faces shift, how the campus angles change with each semester. Notice how you’ve learned to hold the phone steadier, or smile softer, or let the picture be imperfect.

And if you can’t find your first photo, or you’re too afraid to name a last one, that’s okay. The absence is part of the narrative. It means you were too busy living the moment to frame it.

Before this article goes to print, I might walk to the gate and take a photo of the acacias under the streetlights. I don’t know if it’s my last. Maybe I’ll take another tomorrow. But for now, it’s a reminder that every shutter click—answered email or not—is a small act of witness.

So here’s to the photos we share and the ones we keep. The first thing that startled us awake. The last thing that will surprise us later. And to the in-between shots—the messy, beautiful proof that we were here.