As another wave of natural calamities strikes the Philippines, one thing is clear: the state is failing to support its people during critical needs. The aftermath of the 6.9-magnitude earthquake that jolted Cebu Province on the evening of Sept. 30 took mere days to reveal another crack in our national disaster response system—the centralization of resources.

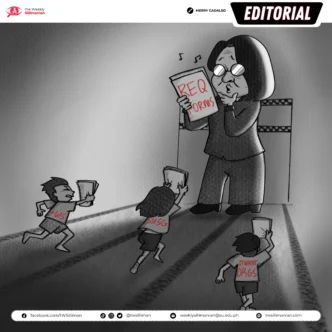

Once the aftershocks had settled, government bodies were quick to mount their relief efforts. In Bogo City, the epicenter of the earthquake, the Department of Social Welfare and Development distributed relief resources worth ₱12.6 million. The Office of the President also vowed to give ₱200 million in assistance to the Cebu provincial government and local government units of quake-stricken cities and municipalities.

Despite these seemingly large-scale efforts, the aid remained unevenly distributed. Survivors in coastal and upland villages continue to appeal as they are burdened by shortages of essential supplies such as food, water, and shelter. Obstructed road sections and damaged bridges also hampered access to affected barangays, the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) reported.

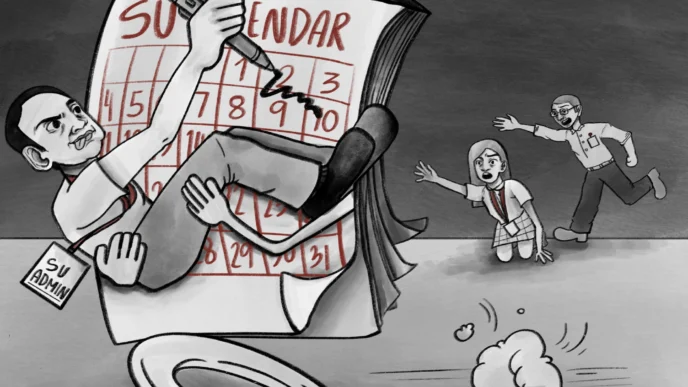

However, the provincial government blamed these delays on heavy traffic leading to northern areas. Cebu Governor Pamela Baricuatro then ordered a centralized collection of relief in designated hubs to prevent road congestion and ensure safety amid continuing aftershocks. But this led to doubled travel times, causing government convoys to slow down the transportation of supplies to remote areas.

While government agencies direct their attention to more densely populated areas, it leaves remote barangays last in line—or entirely overlooked. Displaced individuals and families, who depend solely on the government for assistance, are left waiting for when aid will arrive, if at all.

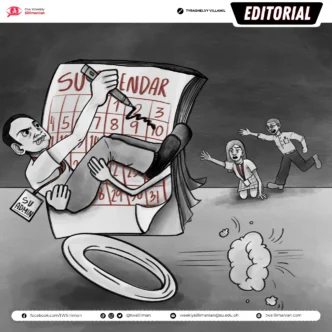

This is the same pattern we’ve seen during the onslaught of typhoon Yolanda in 2013 where severely damaged urban areas like Tacloban were quick to receive aid while remote communities such as Samar, Leyte, and nearby islands went as long as a week without government assistance.

As one of the most calamity-stricken countries, the Philippine government has yet to demonstrate real effort to learn from past lapses and reinvent a disaster response that is community-first.

While the intent to help is there, the system itself continues to fail those who need it most. The Weekly Sillimanian calls the NDRRMC to empower LGUs in setting protocols to mobilize relief efforts, especially in far-flung areas. Assistance to small communities should not be congested at the national levels or lower government agencies alone. It must ensure that help immediately arrives to the most vulnerable population—especially those often out of reach.

The Filipino public must not continue to rely on this top-down approach. The next calamity will again leave the same communities fending for themselves and relief trucks to cross crumbling roads—because the system was never truly designed to reach them first.