By Lealina Evangeline Reyes

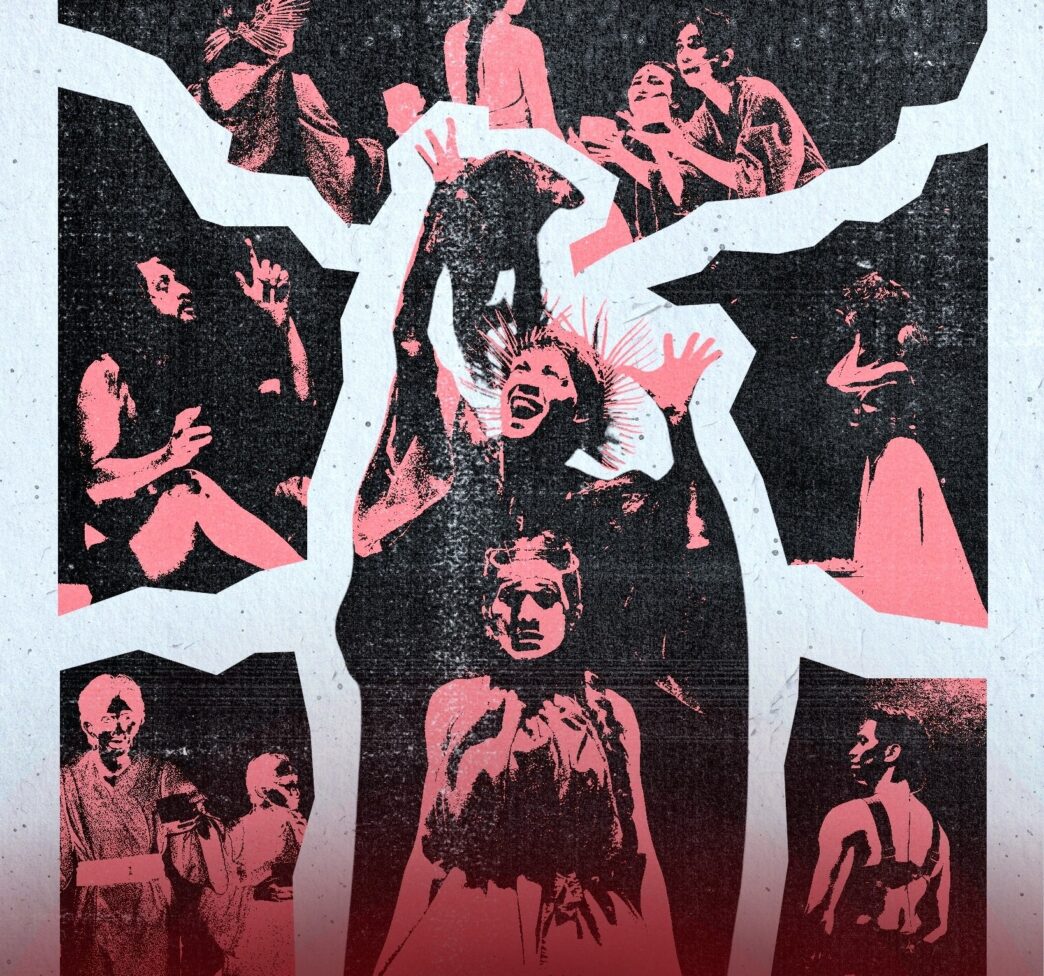

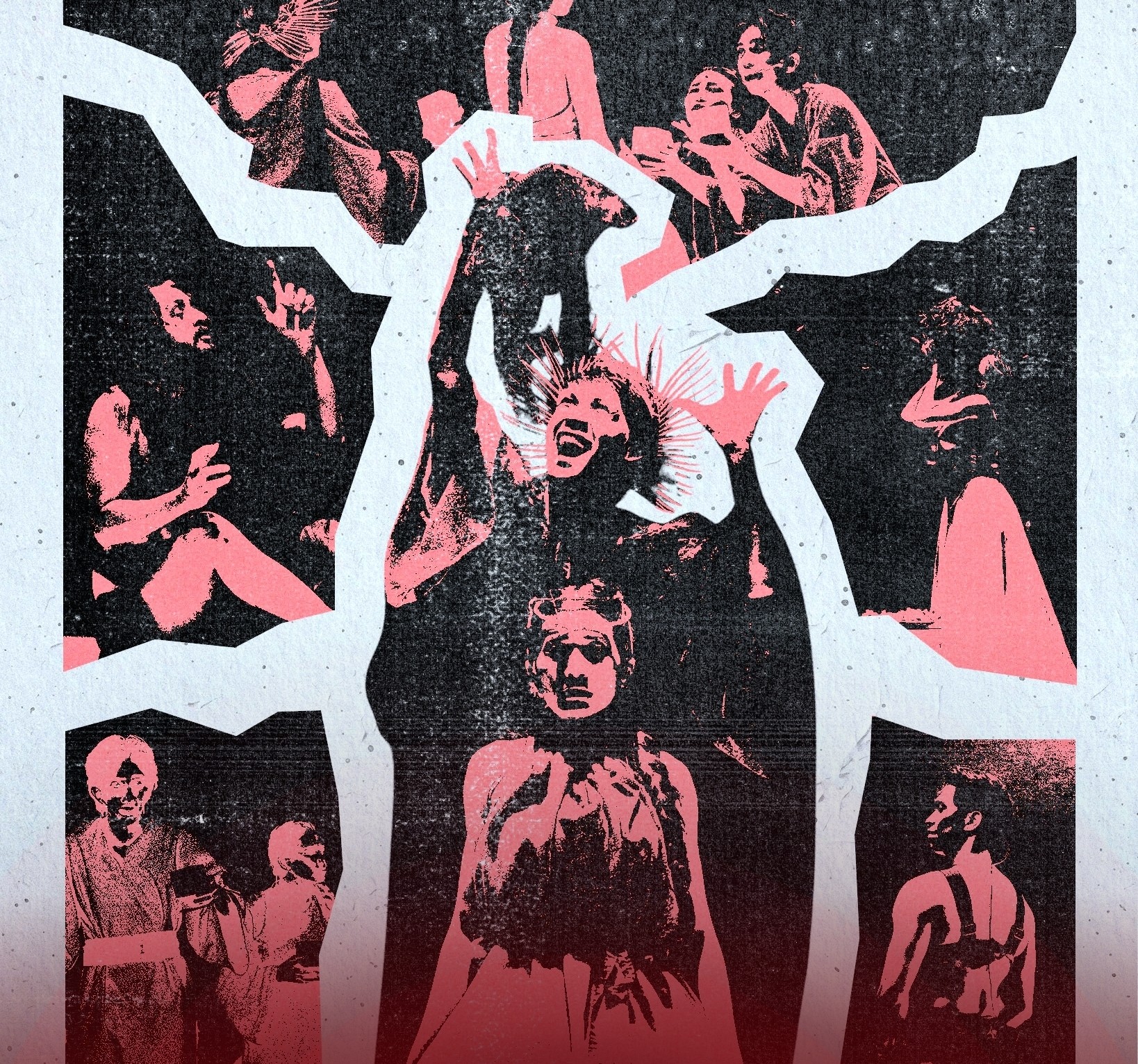

She came face to face with a head on a silver platter, speaking confessions of love, anger, and overwhelming desire. As she lifted the severed part, the audience gasped as they witnessed the woman pull it into a passionate kiss. Was it love? Was it madness? Both and neither was she—Salomé.

In Luce Auditorium, the Bisaya adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s one-act tragedy transported the audience into a world of obsession, power, revenge, and deadly desire. As the story of Salomé unfolded, the theater moved with its rhythmic descent to a constant push-and-pull between laughter, shock, and visual magnificence.

Originally written in French in 1891, Salomé has had countless adaptations from all corners of the world, leaving fingerprints in each stage it has touched. Since then, Wilde’s one-act show has been translated into numerous languages, including English, German, and Spanish.

What is especially captivating about this adaptation of Salomé was not only the exquisite acting but also the unique use of Bisaya in its retelling. Oftentimes, Filipino translations are the roads less traveled by, especially when established—and classic—stories are staged. What is even more infrequent in the Philippine theater arena are Bisaya translations of such plays.

Benjie Kitay, the translator of the play who also starred as King Herod, trekked this risky road of symbols, grammar, and wit. In the end, he held in his hands the uniquely localized version of Salomé, bringing the story closer to home.

The vernacular aspect of the play was what drew an audience to the stage. Traces of Bisaya and Filipino culture embedded themselves in each line with an impressive balance of comedy and drama. But a play does not become a play through script only, and Kitay’s words were brought to life under the direction of Andy Alvarez.

Each delivery of a line, each movement of bodies, and each selection of props and set designs all played crucial roles in the telling of the story. Alvarez’s direction of Salomé explored these individual aspects of the play in a way that each minute detail was important in the sensational tale.

Alvarez also incorporated a sense of intimacy in the play by making the audience part of the show they went to see. This new and quite peculiar seating made the play more impactful compared to the usual house seating, because the audience felt a deeper connection with the characters and the story itself.

With the unique choices made in this adaptation, it came as a surprise to many that it was the directorial debut of Alvarez.

Salomé, the obsessive young girl who demanded the head of Jokanaan from King Herod the Tetrarch, was a character that is quite difficult to understand. Her intentions were masked by naivety, her madness covered by seven layers of sensuality. But she was also a young woman who was navigating her desires in a world where she was seen only as an object to be desired.

Jade Mary Cornelia’s portrayal of Salomé was electrically captivating, piquing great intrigue from the audience. She perfectly captured the character’s impulsivity, naivety, and entitlement as well as her desperation, obsession, and tenacity. Cornelia’s delivery of her lines also allowed the audience to look at who Salomé really is: a princess.

The subtle detail of incorporating English words and phrases to her script, and the other characters echoing them in a rather mocking tone mirrored how rich girls realistically are in the world. The concept of a conyo Salomé was befitting and added layers to her character.

Another pivotal character was Jokanaan, the play’s version of John the Baptist. Despite having a relatively short time to be seen by the audience, this character was understood as important because he was always heard. His was the voice that spoke in the tongue of prophecy that loomed over the play.

When he was finally on center stage, Jokanaan was a striking image that brought eeriness; the kind that compelled you to look even closer. Hope Tinambacan’s portrayal of the character made the audience feel what it would be like to witness a prophet—venerable and frightening. His voice alone was a force to be reckoned with.

After the first few scenes of the play that kept the audience open-eyed, the character that balanced tragedy with comedy arrived. Kitay’s Herod became an instant crowd favorite with his inebriated disposition and his comedic timing. But, as all the other characters in the play, Herod was not a one-sided character present for comedic relief only.

He secretly desired Salomé, promising her everything she wished if she danced for him. When she asked for Jokanaan’s head, he was reluctant and tried to bargain with her. Kitay’s portrayal of Herod’s hesitation to order Jokanaan’s death and the action he took against Salomé after it reminded the audience that at the end of the day, Herod was a man of power.

The final scenes of the play was Salomé’s confession to the decapitated Jokanaan—a chilling and gruesome scene to behold. It was love, it was madness, it was both and neither. It was Salomé the obsessed woman, the grieving lover, the vengeful daughter.

And in a chilling turn of events, Salomé held the head in an embrace as a guard crept behind her, pulling a knife to her throat. He placed his arm around her neck and lifted the blade.

The stage went dark with no lights, no knife, no head, and no Salomé.