Developmental Story on the Looc-Piapi Coastal Project

by Genno Rabaya and Zarelle Villanzana

“Maka reclaim sila kung walay panginabuhi na ma igo, pero kung na’y panginabuhi na ma igo, dili na pwede! Mao na atong ifight!”

(They can reclaim [the area] if no livelihood would be affected, but if there was, it can’t be allowed! That is what we are fighting for!)

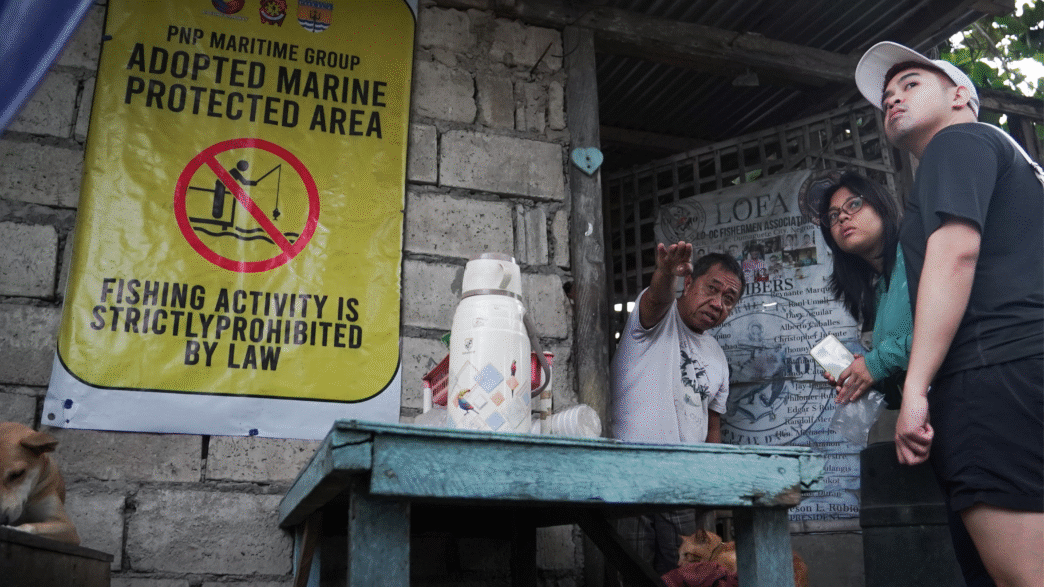

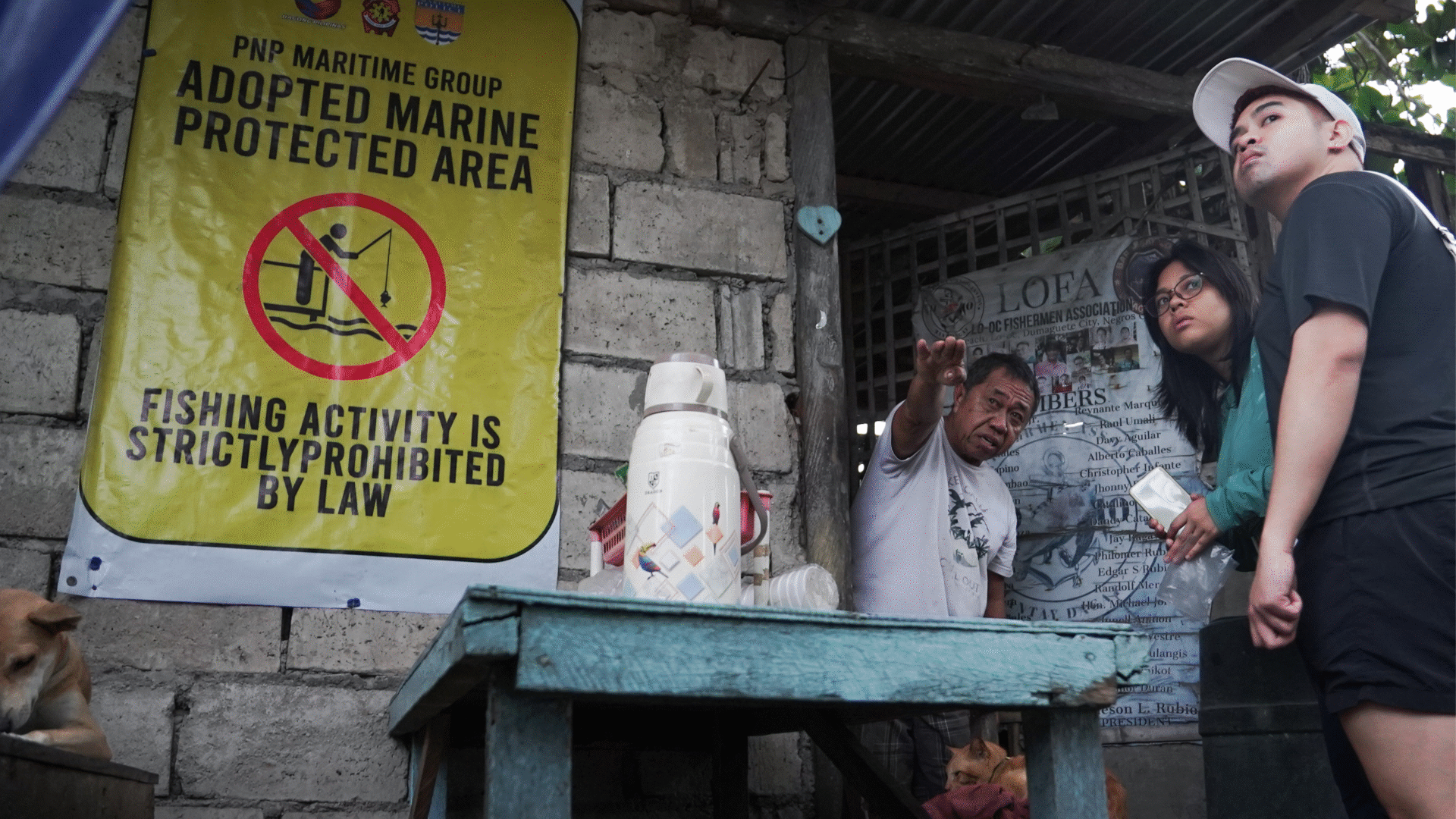

Jameson Rubio, president of the Looc Fishermen Association (LOFA), exclaimed these words in an interview at his home, where the coastal project was in clear view. He pointed to the rubble fronting his house: “Sa una, taas na. Di makita ang dagat.”

(Before, the structure was tall. The sea can’t be seen.)

Due to the height of the concrete, his son, also a fisherman, built an elevated wooden structure, just so they could view the waters again.

“Asa pa man mi managat? Muagi? Ang gobyerno ga hatag namo og para panagat— hukot, sakayan—asa pa man namo na ibutang?”

(Where will we fish? [Where will we] pass through? The government provided us with fishing gear— ropes, boats—where can we even store them?)

These were only some of the plights Rubio revealed concerning the Looc-Piapi Coastal Project. Funded by former Dumaguete City Mayor Felipe Antonio Remollo’s administration and established near the end of his third term in 2025, the project aimed to protect people from storm surges and waves.

It also features possible areas for parking and recreational spaces, similar to those at the Pantawan 2 People’s Park. However, these planned developments overlooked significant factors that could affect their direct community.

“Wala na siya gipa agi og public hearing. Diretso lang,” Rubio continued. “Naa pa silay ikaduha na gi propose na [project], ilang ipadayon dira kay ipasunod sa PPA.”

(The project did not go through a public hearing. It was implemented immediately.) (They have a second proposed project too, they want to follow it to the PPA [Philippine Port Authority].)

Rubio’s association, LOFA, was established in 2010, and was legally registered the following year.

LOFA did not consent to this project, Rubio claimed, and neither the Barangay. “Kami man gipasanginlan kiniadto ni mayor nga ang iyang proyekto, kami ang nakaingon ngano wala mahidayon.”

Despite these sentiments, the existence of rocks, steel bars, and cement rising along the coast of Barangays Looc and Piapi proved otherwise. The construction was secretly ongoing.

Before, engineers would come to measure the area regularly on Saturdays or Sundays, when the barangay was not working. They would arrive during lunchtime with their materials, and one glimpse exchanged by both parties would confirm their acknowledgment of what was about to happen.

“May permiso na ba kayo galing sa Barangay?” Rubio would ask the engineers, and they would respond with a negative.

(Do you have the Barangay’s permission?)

“Babakuran ‘to, Tay,” one of the engineers would tell him. “Tay, kung matuloy ‘to, kawawa, wala na yung dagat,”

(They are fencing this off, Tay.) (Tay, if this proceeds, what a pity, the sea would be no longer.)

There is an unnamed force that allows for the developments to proceed, and neither the fisherfolk nor the engineers get a say in it.

“Kami, igo ra pud mi gapakabana,” Rubio expressed.

([As locals], we are just showing concern.)

Beyond concerns for the local fisherfolks’ well-being, Rubio also emphasized a key detail of their doubts on the coastal extension: the project subtly edges along a marine sanctuary. According to Rubio, corals and a vibrant marine life thrive in the area, which are put at risk by the construction of the project.

“Makita ang corals bisag musalom ka. Buhi pa jud hangtud karun,” Rubio testifies. “Kanang sanctuary, di jud siya pa-dagatan. Mao na siyang itloganan sa isda.”

(The corals are visible even if you just swim along the area. They’re alive until now.) (Even fishing at the sanctuary is prohibited. That’s where the fish lay their eggs.)

He refers to the Looc Marine Sanctuary and Reservation Area, supposedly one of the 46 MPAs (Marine Protected Areas) in Negros Oriental, to be declared “reclamation-free zones,” which means all foreshore and offshore reclamation activities in such areas are banned.

Rubio shared that even the Department of Public Works and Highways, if they were to admit, was puzzled why it got approved. With the existing policy, Ordinance No. 29 Series of 2021, the area should remain protected.

This was highlighted in 2021, when late Governor Roel Degamo argued that there were no coral reefs in Dumaguete City. Multiple environmental experts, however, shut this accusation down through various posts on social media with proof of the vibrant life underwater.

“Sa Piapi karun, akong nadunggan, nag-propose na pud sila ug gama og sanctuary dira,” Rubio shared. “Maayo na, [recognizing] sa mga sanctuary, pero bantayan lang pud. Lain pud nang magbutang ug marine sanctuary pero layo kaayu sa among mga bantay dagat.”

(In Piapi right now, I heard, they are proposing to make a sanctuary too.) (That’s good, to recognize a sanctuary, but it should be safeguarded. It would be strange to put a marine sanctuary but distance the people who guard the seas.)

The initial decision by Rubio to proceed with the project was derived from an unclear picture, he claimed. They were originally informed that another boulevard was set to rise in the constructed area, with the possibility of opportunities for vendors to settle and tourism to boost in their locality. Little did they know of the full extent of the Philippine Port Authority’s involvement and the possible road access connecting to the port.

“Mao bitawng nisugot ko una kay abi nako’g boulevard. Akong huna-huna, maninda gihapon ang mga taga-diri, so naay panghinabuy-an. Pero lain man diay ning ga plano ani.”

(That is why I initially agreed to it, because I thought they were gonna construct a boulevard. My thought was that residents here would continue to sell for their livelihood. But the developers had other plans for this.)

Rubio recognized that it is high time for Dumaguete City to progress with developments. However, as someone receiving the brunt of the project, development should not come at the expense of others.

“Para nako, di man mali ang development, pero kanang diha, dili na unta. Daghan kaayu ang maapekto[han] ana. Daghan gyud kaayu.”

(For me, development is not wrong but [the project] over there, it should not happen. Many would be affected by it. There are really many.)

While significant to the fisherfolk, the consequences of the shoreline project are not exclusive to them. A deeper dive into the circumstances of nearby stakeholders, such as the business owners and the settlers of the area, is necessary to understand the project’s intent and effect as a whole.

How each of their stories would conclude can only be unraveled from the shoreline.

This is a developing story.